September 4, 2025 by Joe Ross

Numerous states and regions are investigating or openly advancing initiatives to bring city and county public safety users onto common regional land mobile radio systems to improve interoperability and reduce emergency communications expenses. The benefits of shared systems are immense. While many smaller counties, cities, and towns struggle to afford the capital and operational costs of achieving public safety grade communications, by banding together, a shared system’s resiliencies can benefit all users – especially when joining members can make direct investments to augment coverage and capacity where needed. Frequently, smaller municipalities will operate conventional radio networks where users operate on a static frequency transmitted by a unique base station facility. Regional and statewide systems typically use trunking technology that dynamically assigns frequencies to talkgroups; support more end users; and have additional functional, security, and cost benefits.

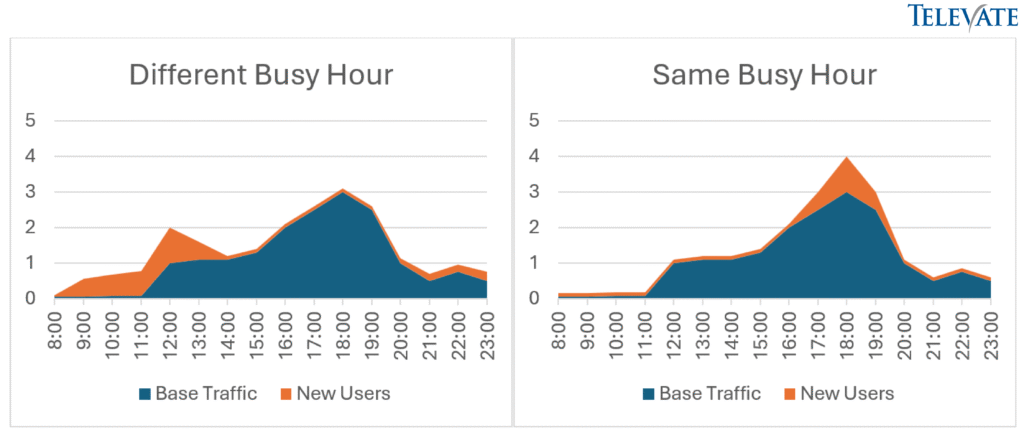

But there are challenges in making this happen. First and foremost, it can be complex to determine how new users will impact a regional system and whether they will cause a degradation in the grade of service (GOS) for a trunking system. Many systems, especially those that have upgraded to P25 Phase 2 – TDMA, have excess capacity that can accommodate the additional usage. But in many cases, a statewide system that adds local users may increase the total user base by multiple times the current number of users – and the usage may then scale significantly and be unable to support the entire user base at public safety standards. Frequently, new tenants on a statewide or regional system are unlikely to have reliable usage data from their (generally) conventional radio system (although if they have voice recorders for all of their public safety channels, they may be able to build system usage data). The absence of this key information makes it more difficult to estimate how much additional traffic the new public safety users will add to the network. Ultimately, the measure that matters most is the busy hour demand these new users will place on the network. If these new users’ peak usage occurs at the same time as the existing users (which is likely during joint agency incident responses), then the new groups’ busy hour traffic is additive. However, it’s also possible that a completely unrelated event in the same area might result in additional usage/activity that may or may not align with the typical busy hour traffic. The following figure presents two of the possible ways different users’ traffic may aggregate in a given area.

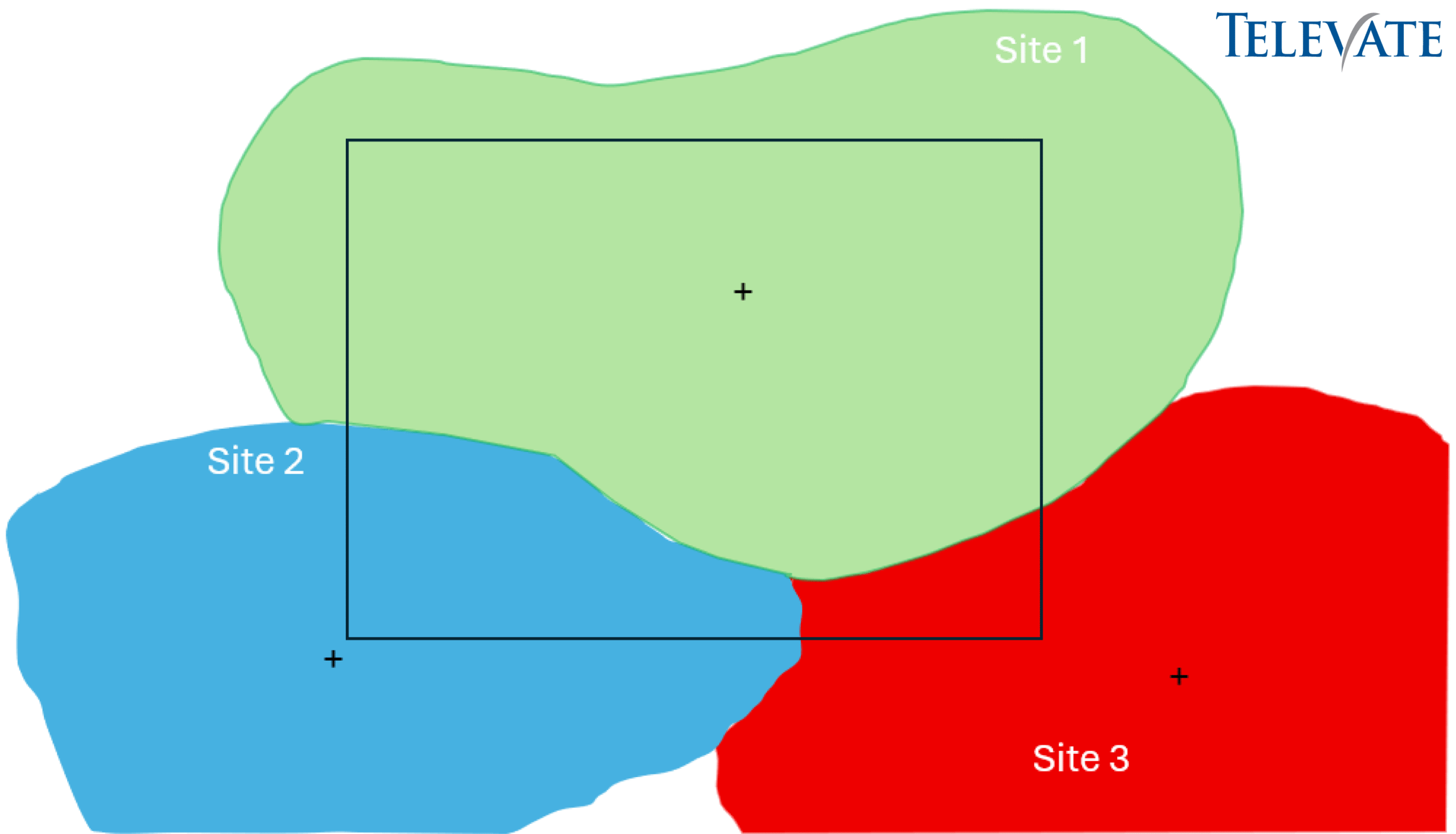

Many in public safety plan for that worst-case scenario so they may assume the usage of all agencies will peak at the same time and therefore require additional capacity. But that only addresses the time-based effects of the traffic. There are also spatial aspects of the traffic. A city’s traffic is predominately generated within the city, and a county’s traffic is predominately generated within the county. There may be some instances where a team from the city might provide mutual aid two counties away, but most of the users’ traffic from these city and county agencies are generated within their home jurisdiction. And, most mutual aid will occur close to the borders of the city. As a result, the bulk of city or county users’ time will be spent within the county/city plus some buffer area. Whenever their users key up on their talkgroups, all sites where users are affiliated will transmit their communications. Therefore, if three sites serve a county and users are within the service footprint of all three sites, then the county’s traffic will require resources at all three sites.

In the example illustrated above, there is one primary site (Site 1) that serves the county, but two others also provide service to parts of the county, with Site 3 serving only a small portion. Site 3 serves predominantly other counties, but the small area in the southeastern portion of the county may contain users during a peak traffic event. The probability of that occurring likely depends on the public safety activity in that portion of the county (probably correlated with the population in that area). So, modeling for the capacity impacts of this particular county based on this limited area might, on one hand “discount” the county’s contribution to Site 3, or, the worst-case scenario may apply the county’s entire usage to the area.

Unless the sites above are simulcast, this factor then duplicates city or county’s law enforcement, fire/rescue, or other agency traffic at each of the sites providing service to those county users. System operators may also want to model mutual aid usage by the county further from the county’s borders as well.

The process then involves determining the sites that cover each city or county, and then aggregating all of the cities’ and counties’ traffic across all of the system’s sites to determine the net load on the system at each site. Then, using traffic engineering models, the number of talkpaths and channels can be determined per site to assess the overall impact of all prospective customers of the regional or statewide system. Televate has developed software to facilitate this process, even allowing for the selection of cities and counties expected to join a regional system. Let me know if you are interested in our services to evaluate whether your system has the capacity to support additional users. We can even consider whether your system’s explicit channels will prevent you from achieving the necessary capacity to accommodate all users. We can customize our model to meet many different scenarios and perspectives. Contact me at jross@televate.com to start the conversation and to find out more to assess the feasibility of expanding your system.